Major TV Debuts - 1995 Xena: Warrior Princess

Major TV debuts from the year you were born

As the landscape of TV continues to shift, it’s always a good time to pause and look at the medium’s history. Although the latest buzzy Netflix show dominating everyday conversations is normal, television is one of the youngest art forms around. The first American TV station began broadcasting in 1928, but television didn’t really start growing into the influential, widespread phenomenon that it is now until the 1950s.

Stacker conducted manual research to compile a list of notable television debuts from the past 70 years, listing one show for each year and using a variety of unique sources. When selecting TV shows to add, Stacker looked for series that were not just popular when they were airing, but remain influential and iconic in pop culture to this day.

1995: Xena: Warrior Princess

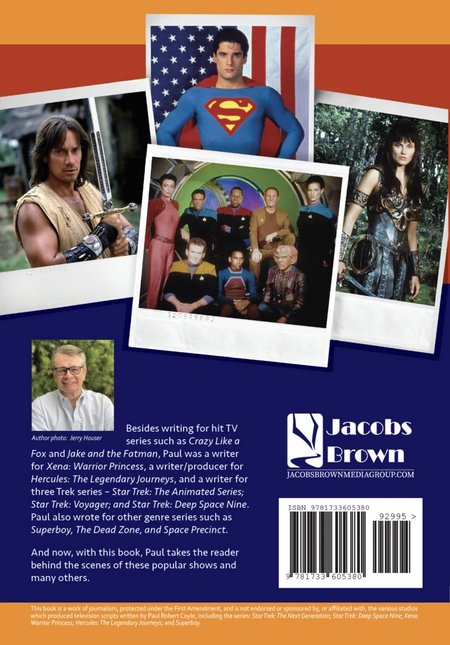

Originally greenlit as a spinoff of the TV series “Hercules: The Legendary Journeys,” this fantasy series follows Xena, played by Lucy Lawless, a powerful warrior who seeks to resolve her past wrongs by helping those in need. “Xena: Warrior Princess” gained a particularly strong cult following, with TV Guide naming it one of the top cult shows ever made.