NZ Herald

8 September 2020

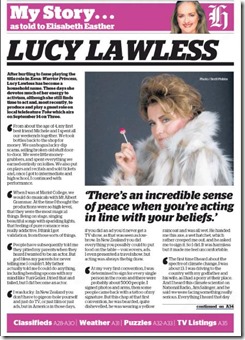

NZ Herald: My Story. . .Lucy Lawless as told to Elisabeth Easther

After hurtling to fame playing the title role in Xena: Warrior Princess, Lucy Lawless has become a household name. These days she devotes much of her energy to activism, although she still finds time to act and, most recently, to produce and play a guest role on local telefeature Toke which airs on September 14 on Three.

From about the age of 4, my first best friend Michele and I spent all our weekends together. We took bottles back to the shop for money. We ran bogus lucky-dip scams, selling broken old stuff door-to-door. We were little moneygrubbers, and spent everything we earned entirely on lollies. We also put on plays and recitals and sold tickets and, once I got to intermediate and high school, I continued with performance.

‘ When I was at Marist College, we would do musicals with Mt Albert Grammar. At the time I thought the productions were so high-level, that they were the most magical things. Being on stage, singing beautiful songs with sparkling lights, that feeling of pure romance was really addictive. I think I got validation, from those sorts of things.

‘ People have subsequently told me they pitied my parents when they heard I wanted to be an actor. But god bless my parents for never telling me I couldn’t. My father actually told me I could do anything, including bending spoons with my mind like Yuri Geller. I tried that and failed, but I did become an actor.

‘ I was lucky. In New Zealand you don’t have to pigeon-hole yourself and just do TV, or just film or just ads, but in America in those days, if you did an ad you’d never get a TV show, as that was seen as lowbrow. In New Zealand you did everything you possibly could to put food on the table — voiceovers, ads. I even presented a travel show, but acting was always the big draw.

‘ At my very first convention, I was determined to sign for every single person in the room and there were probably about 5000 people. I signed photos and arms, then some people came back with a tattoo of my signature. But this chap at that first convention, he was bearded, quite dishevelled, he was wearing a yellow raincoat and was all wet. He handed me this axe, a wet hatchet, which rather creeped me out, and he asked me to sign it. So I did. It was harmless but it made me feel uncomfortable.

The first time I heard about the spectre of climate change, I was about 13. I was driving to the country with my godfather and his wife, as I had a pony at their place. And I heard this climate scientist on National Radio, Jim Salinger, and he said we were facing something really serious. Everything I heard that day made sense; it fell with the weight of anvils. It felt like truth and I wasn’t able to shrug it off.

‘ Years later I played a role in the telefeature The Rainbow Warrior. My character was based on Bunny McDiarmid, one of the Greenpeace crew members. When I met her, I was blown away by her and her partner Henk. They’re nothing like the crazy hippies you see represented on TV. They’re erudite and funny, compassionate and wise. There’s nothing airy-fairy about these people, they’re the most practical people on earth. They told me about the Sign On campaign and I became involved because, what use is it to be a public entity if you’re not using it for good?

‘ A big part of my upbringing, the whole ethos at Marist Sisters’ College, is that you are your brother’s keeper. You take care of the little guy. My mum and dad were like that too, so it felt like the natural thing to do. When Dad died while I was in the Arctic on a protest against oil drilling, it was a very weird feeling. Should I go home for the funeral or go on with the mission?

‘ I decided I couldn’t do anything for big Frank, but little Frank, his grandson, I could do something for. Even though Dad didn’t approve of my activism. He thought I was a rabble-rouser and it took a report on climate change by the Pope for my Dad to think it was legitimate. I struggled with Dad’s view of my activism, it hurt that he didn’t trust me to be doing it for the right reasons and not just politics.

‘ Because I’m a ‘good girl’ when I’m protesting. I mind more about being arrested than falling and dying. But I never feel that vulnerable, I just get on with it. There’s an incredible sense of peace when you’re acting in line with your beliefs, even if you’re doing something dangerous or against the law.

‘ The worst moment for me on a protest was before we broke into Port of Taranaki. I knew I was about to cross a line — and that threshold, it went on for ages. I wanted to panic, to freak out and run away, but that wasn’t an option. I couldn’t let those people down.

‘ But we kept not being arrested. That was so shocking. We climbed up the tower on the drill ship in our overalls, I was so stressed I was mouth-breathing. The other female with us, Viv Hadlow, she had a massive tower of dreadlocks on her head, and a safety helmet perched on top so she looked like Marge Simpson. And I’m thinking, how are we not going to be arrested? ‘Gidday fellas’, we’re saying and they’re saying, ‘yeah gidday’ back. We kept not being arrested much longer than I expected, and all I remember is peanuts and chocolate.

‘ There were seven of us on this platform, a couple of spidermen hanging banners and my whole perception of time and space warped to cope with the situation. I became camp mother, and I’d tidy up and make sure everyone wore sunscreen, and do the interviews. Then it was, ‘my god, where did that day go?’ We put our beds on this thing the size of a hearthrug, seven of us sleeping on this savage grille that’s about as comfortable as bicycle pedals. It was brutal on the knees. When I got home from the protest, I walked through our house thinking, ‘oh my god, there’s too much space’. I was swimming through a miasma of space. What are all these chairs for? You don’t need all these chairs.

‘ New Zealanders have a lot of native good sense, and we must not let go of that. These agitators, these supposed grown-ups, politicians like Gerry Brownlee and Winston Peters, they’re fomenting mistrust and anarchy. When people are afraid, and you start putting out earworms — and the whole community is a little bit afraid right now — you’re fomenting social unrest. It’s an antisocial thing to do and I call them on it. Shame on them. That is not what New Zealanders are about.